Have Questions? Contact Us.

Since its inception, NYCLA has been at the forefront of most legal debates in the country. We have provided legal education for more than 40 years.

Appellate Division – First Department

Daniel Hernandez and Nevin Cohen,

Lauren Abrams and Donna Freeman-Tweed,

Michael Elsasser and Douglas Robinson,

Mary Jo Kennedy and Jo-Ann Shain,

and Daniel Reyes and Curtis Woolbright,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

-against-

Victor L. Robles, in his official capacity as

City Clerk of the City of New York,

Defendant-Appellant.

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

New York County Lawyers’ Association

14 Vesey Street

New York, NY 10007

212-267-6646

National Black Justice Coalition

17251 Street, NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20006

202-349-3755

Metropolitan Black Bar Association,

299 Broadway, Suite 1203A

New York, NY 10007

212-964-1645

OF Counsel:

|

Ivan J. Dominguez |

|

|

Kathryn Shreeves |

|

|

Jean M. Swieca |

Attorneys for Amici Curiae |

Reproduced on Recycled Paper

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS |

|

|

PAGE |

|

|

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES |

iii |

|

APPENDIX |

Viii |

|

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI |

1 |

|

A. The New York County Lawyers’ Association |

1 |

|

B. The National Black Justice Coalition |

3 |

|

C. The Metropolitan Black Bar Association |

4 |

|

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT |

4 |

|

ARGUMENT |

6 |

|

I. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND |

6 |

|

A. Interracial Marriage Was Prohibited In This Nation For More Than 300 year |

6 |

|

B. Marriage Prohibitions Extended To Numerous Racial Groups |

11 |

|

C. Anti-Miscegenation Laws Enjoyed Vast Popular Support |

15 |

|

II. THE CITY’S ARGUMENTS ATTEMPTING TO CIRCUMSCRIBE THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO MARRY DO NOT WITHSTAND SCRUTINY |

15 |

|

A. Contemporary “Popular Opinion” Cannot Define The Fundamental Right To Be Free From Unwarranted Governmental Intrusion |

16 |

|

1. Fundamental Rights Should Not Be Defined Narrowly to Incorporate the Challenged Governmental Restriction |

17 |

|

2. The City’s Focus on the Historical Recognition of the Right to Marry Is Overly Narrow |

74 |

|

3. The Prevalence of Existing Laws is Irrelevant |

11 |

|

PAGE |

|

|

B. The City’s “Applied Equally” Argument Does Not Support The Prohibitions On Marriage Between Individuals Of The Same Sex |

29 |

|

CONCLUSION |

33 |

|

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES |

|

|

PAGE(S) |

|

|

CASES: |

|

|

Bowers v Hardwick, 478 US 186 [1986] |

27-28 |

|

Brause v Bureau of Vital Statistics, No. 3AN-95-6562 Cl, 1998 WL 88743 [Alaska Super Ct Feb. 27,1998], aff’d sub nom Brause v Alaska Dept, of Health & Soc. Servs., 21 P3d 357 [Alaska 2001] |

25 |

|

Britell v Jorgensen (In re Takahashi’s Estate), 113 Mont 490, 129 P2d 217 [1942] |

25-26 |

|

Dodson v Arkansas, 61 Ark 57,31 SW 977 [1895] |

10, 14 |

|

Doe v Coughlin, 71 NY2d 48 [1987], cert, denied 488 US 879 [1988] |

23 |

|

Green v Alabama, 58 Ala 190 [1877] |

10, 14, 30 |

|

Griswold v Connecticut, 381 US 479 [1965] |

16 |

|

Henkle v Paquet (In re Paquet’s Estate), 101 Or 393, 200 P 911 [1921] |

28,31 |

|

Hernandez v Robles, 7 Misc 3d 459 [Sup Ct, NY County 2005] |

passim |

|

Indiana v Gibson, 36 Ind 389 [1871] |

10, 14 |

|

Jackson v City & Cty of Denver, 109 Colo 196, 124 P2d 240 [1942] |

31 |

|

Kentucky v Wasson, 842 SW2d 487 [Ky 1992] |

19 |

|

PAGE(S) |

|

|

Kinney v Virginia, 71 Va 858 [1878] |

9-10, 14 |

|

Kirby v Kirby, 24 Ariz 9, 206 P 405 [1922] |

28 |

|

Lawrence v Texas, 539 US 558 [2003] |

21,27-28 |

|

Lee v Giraudo (In re Monks ’ Estate), 48 Cal App 2d 603, 120 P2d 167 [Ct App 1941], appeal dismissed 317 US 590 [1942] |

28 |

|

Levin v Yeshiva Univ., 96 NY2d 484 [2001] |

23 |

|

Lonas v Tennessee, 50 Term 287 [1871] |

passim |

|

Loving v Virginia, 388 US 1 [1967] |

passim |

|

Mary of Oakknoll v Coughlin, 101 AD2d 931 [3d Dept 1984] |

23 |

|

McLaughlin v Florida, 379 US 184 [1964] |

32 |

|

Meyer v Nebraska, 262 US 390 [1923] |

20 |

|

Missouri v Jackson, 80 Mo 175 [1883] 10, 14, 30-31 |

10,14,30-31 |

|

Naim v Naim, 197 Va 80, 87 SE2d 749, vacated and remanded 350 US 891 [1955], adhered to 197 Va 734, 90 SE2d 849 [1956] |

13, 14 |

|

People v Harris, 77 NY2d 434 [1991] |

19-20 |

|

PAGE(S) |

|

|

People v Onofre, |

|

|

51 NY2d 476 [1980], cert denied 451 US 987 [1981]. |

18 |

|

People v Shepard, |

|

|

50 NY2d 640 [1980] |

23 |

|

Perez v Lippold, |

|

|

32 Cal 2d 711, 198 P2d 17 [1948] |

passim |

|

Pierce v Society of Sisters of Holy Names of Jesus & Mary, |

|

|

268 US 510 [1925] |

20 |

|

Planned Parenthood v Casey of Southeastern Pa., |

|

|

505 US 833 [1992] |

passim |

|

Scott v Georgia, |

|

|

39 Ga 321 [1869] |

10, 14 |

|

Skinner v Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, |

|

|

316 US 535 [1942] |

6, 20 |

|

Turner v Safley, |

|

|

482 US 78 [1987] |

20-21 |

|

Zablocki v Redhail, |

|

|

434 US 374 [1978] |

passim |

|

STATUTES & OTHER AUTHORITIES: |

|

|

49 Cong Rec 502 [Dec. 11,1912] |

10-11 |

|

NY Const: |

|

|

Preamble |

19 |

|

art I, § 6 |

18 |

|

art I, § 1 |

18 |

|

1862 Or. Laws §63-102 |

12 |

|

1866 Or. Laws §23-1010 |

12 |

|

PAGE(S) |

|

|

Charlotte Astor, Gallup Poll: Progress in Black/White Relations, But Race is Still an Issue <usinfo.state.gov/joumals/ itsv/0897/ijse/gallup.htm> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

15,28 |

|

David H. Fowler, Northern Attitudes Toward Interracial Marriage: Legislation & Public Opinion in the Middle Atlantic & the States of the Old Northwest, 1780-1930 [1987] |

8 |

|

Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical & Practical [1854] |

8 |

|

Randall Kennedy, Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity & Adoption [2003] |

12-13 |

|

Nicholas D. Kristof, Marriage: Mix and Match, NY Times, Mar. 3, 2004, at A23 |

15 |

|

Rachel F. Moran, Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race & Romance [2001] |

passim |

|

Denise C. Morgan, Jack Johnson: Reluctant Hero of the Black Community, 32 Akron L Rev 529 [1999] |

11 |

|

Note, Litigating the Defense of Marriage Act: The Next Battleground for Same-Sex Marriage, 117 Harv L Rev 2684 [2004] |

25 |

|

Peggy Pascoe, Miscegenation Law, Court Cases & Ideologies of “Race ” in Twentieth Century America, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

11 |

|

Peggy Pascoe, Why the Ugly Rhetoric Against Gay Marriage is Familiar to ThisHistorian of Miscegenation [2004] <hnn.us/articles/4708.html> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

27 |

|

Charles Frank Robinson II, Dangerous Liaisons: Sex & Love in the Segregated South [2003] |

7,11 |

|

PAGE(S) |

|

|

Leti Volpp, American Mestizo: Filipinos & Anti-Miscegenation Laws in California, in Mixed Race America & the Law: A Reader [Kevin R. Johnson ed., 2003] |

12 |

|

Peter Wallenstein, Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage & Law—An American History [2002] |

6, 7, 13 |

|

Carter G. Woodson, The Beginnings of Miscegenation of the Whites and Blacks, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

7 |

|

Kansas St Hist Soc’y web site <www.kshs.org/publicat/history/ 1999winter_sheridan.htm> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

13 |

|

John Mercer Langston Bar Assn web site <www.jmlba.org/JMLBio.htm> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

13 |

|

TheFreeDictionary.com, Miscegenation <www.encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/ miscegenation> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

15 |

|

The Miscegenation Hoax < www.museumofhoaxes.com/ miscegenation. html> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

9 |

|

Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Miscegenation <en.wikipedia.org/.wiki/Miscegenation> [last accessed August 3, 2005] |

9 |

|

APPENDIX |

|

|

TAB |

|

|

Excerpts from Peter Wallenstein, Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage & Law—An American History [2002] |

A |

|

Excerpts from Rachel F. Moran, Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race & Romance [2001] |

B |

|

Excerpts from Carter G. Woodson, The Beginnings of Miscegenation of the Whites and Blacks, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

C |

|

Excerpts from Charles Frank Robinson II, Dangerous Liaisons: Sex & Love in the Segregated South [2003] |

D |

|

Excerpts from David H. Fowler, Northern Attitudes Toward Interracial Marriage: Legislation & Public Opinion in the Middle Atlantic & the States of the Old Northwest, 1780-1930 [1987] |

E |

|

Excerpts from Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical & Practical [1854] |

F |

|

Excerpts from Peggy Pascoe, Miscegenation Law, Court Cases & Ideologies of “Race” in Twentieth Century America, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

G |

|

Excerpts from Leti Volpp, American Mestizo: Filipinos & Anti-Miscegenation Laws in California, in Mixed Race America & the Law: A Reader [Kevin R. Johnson ed., 2003] |

H |

|

Excerpts from Randall Kennedy, Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity & Adoption [2003] |

I |

Amici Curiae, the New York County Lawyers’ Association (“NYCLA”), the National Black Justice Coalition (“NBJC”) and the Metropolitan Black Bar Association (“MBBA”) submit this brief in support of Justice Doris Ling-Cohan’s decision below in Hernandez v Robles (7 Misc 3d 459 [Sup Ct, NY County 2005]) rejecting New York’s prohibition on marriage between same-sex partners as unconstitutional under New York’s Constitution. For the reasons set forth herein and in the Record, the decision below should be affirmed.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI

The New York County Lawyers’ Association

NYCLA is a not-for-profit membership organization of approximately 8,500 attorneys practicing primarily in New York County, founded and operating specifically for charitable and educational purposes. NYCLA’s certificate of incorporation specifically provides that it is to seek reform in the law and do what it deems in the public interest and for the public good.

In 1907, a group of lawyers gathered in Carnegie Hall to address the prospect of forming a bar group where heritage and politics were not obstacles to inclusion. The bar leaders who met were determined to create, in the words of Hon. Joseph H. Choate, who would become president in 1912, “the great democratic bar association of the City [where] any attorney who had met the rigid standards set up by law for admission to the bar should, by virtue of that circumstance, be eligible for admission.” Adherence to professional standards alone would determine eligibility.

When NYCLA was founded, it was the first major bar association in the United States of America that admitted members without regard to race, ethnicity, religion or gender. Since its formation in 1908, NYCLA has played a leading role in the fight against discrimination under local, state and federal law. Although various factors inspired NYCLA’s creation, none was as strong as its rejection of the “selective membership” that other bar associations employed to deny large groups of lawyers the opportunity to participate in bar association activities. Throughout its history, NYCLA’s bedrock principle has been the inclusion of all who wish to join the active pursuit of legal system reform.

Consistent with its opposition to discrimination in the legal profession, in 1943 NYCLA refused to renew its affiliation with the American Bar Association because it would not admit African-American lawyers. And in December 2003, the NYCLA Board of Directors adopted a resolution endorsing full equal civil marriage rights for same-sex couples.

NYCLA’s endorsement of equal civil marriage rights for same-sex couples grew out of its concern that an entire class of New York couples and their families lack the protections afforded to families led by heterosexual couples. To ensure that all rights, benefits and responsibilities attendant to civil marriage are available to same-sex couples in New York, NYCLA submits that it is necessary to extend civil marriage rights to same-sex couples without diluting these rights through piecemeal legislation or the ambiguous “civil union” or “domestic partnership.” In the absence of state-recognized marriage rights, same-sex couples are relegated to second-class citizenship when they are denied the equal rights that are available to heterosexual couples and their families.

B The National Black Justice Coalition

NBJC is a non-profit, civil rights organization of black lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people and allies dedicated to fostering equality. NBJC has more than 3,000 members nationwide and advocates for social justice by educating and mobilizing opinion leaders, including elected officials, clergy and media, with a focus on black communities. Black communities have historically suffered from discrimination and have turned to the courts for redress. With this appeal, we turn to the courts again. The issue presented by this appeal has significant implications for the civil rights of black lesbians and gay men in this State – whether they will receive equal treatment under the law and the legal recognition and protections of marriage for their relationships and families. NBJC envisions a world where all people are fully empowered to participate safely, openly and honestly in family, faith and community, regardless of race, gender- identity or sexual orientation.

C The Metropolitan Black Bar Association

MBBA is a New York City-wide organization of mainly black and other minority attorneys dedicated to aiding the progress of attorneys of color and to assisting the progress of the legal profession generally. MBBA was formed 21 years ago through a merger of two of the oldest minority bar associations in the country: the Harlem Lawyers Association, formed in 1921, and the Bedford- Stuyvesant Lawyers Association, formed in 1933. Since the founding of MBBA’s predecessor organizations—at a time when minority attorneys were prevented from joining most mainstream bar associations—black attorneys have been at the forefront of the fight against discrimination on all fronts. MBBA is committed to equal justice for all and preventing state-sanctioned discrimination and, accordingly, the issue presented by this appeal is of extreme importance to MBBA’s member attorneys and the community it serves.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This Nation has a history of discrimination that was once commonplace and acceptable, but is resoundingly rejected today. Other types of discrimination continue, such as that in issue now before this Court: the prohibition on civil marriage between same-sex couples. The current prohibition on marriage between individuals of the same sex is rationalized today based on its longstanding history and supposed equal application to men and women.

For centuries, these same rationalizations were used to justify the prohibition of interracial marriage—a prohibition that no one today would defend as even arguably constitutional. Thus, in any analysis of today’s restrictions on the right to marry for same-sex couples, we must be mindful of this Nation’s history of discriminating against couples of different races. At the core of both prohibitions lies the violation of an individual’s right to marry. On February 4, 2005, Supreme Court Justice Doris Ling-Cohan in the decision below, Hernandez v Robles (7 Misc 3d 459 [Sup Ct, NY County 2005]), rejected New York’s prohibition on marriage between same-sex partners as unconstitutional under New York’s Constitution. The decision below recognized the striking similarity in the nature of the history of racial discrimination in the realm of restrictions on marriage partners:

“An instructive lesson can be learned from the history of the anti-miscegenation laws and the court decisions which struck them down as unconstitutional. The challenges to laws banning whites and non-whites from marriage demonstrate that the fundamental right to marry the person of one’s choice may not be denied based on longstanding and deeply held traditional beliefs about appropriate marital partners…. [T]he United States Supreme Court was not deterred by the deep historical roots of anti-miscegenation laws [(Loving v Virginia, 388 US 1,7, 10 [1967])]; their continued prevalence [(id. at 6 n 5)]; nor any continued popular opposition to interracial marriage. [(Id. at 7)]. Instead, the Court held that ‘[u]nder our Constitution, the freedom to marry or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State,’ declaring that ‘marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival.’ [(Id. at 12 (quoting Skinner v Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 US 535, 541 [1942])].”

(Id. at 461-462).

This brief provides a detailed historical background of the prohibition on interracial marriage in the United States and an analysis of judicial opinions that ultimately recognized the prohibition as an unconstitutional violation of an individual’s fundamental right to marry. Viewed against this background, Amici respectfully request that this Court affirm that the prohibition on civil marriage between same-sex couples is also unconstitutional.

ARGUMENT

I.HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Interracial Marriage Was Prohibited In This Nation For More Than 300 Years

The interracial marriage prohibition was deeply rooted in our Nation’s history and tradition. Statutes prohibiting interracial marriage were enforced in American colonies and states for more than three centuries. (See Peter Wallenstein, Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage & Law—An American History 253-254 [2002], annexed to the Appendix as Tab A). The first anti-miscegenation law was enacted in Maryland in 1661. (Rachel F. Moran, Interracial Intimacy: the Regulation of Race & Romance 19 [2001], annexed to the Appendix as Tab B). Virginia followed suit soon after. {See id.).

Interracial marriage was so far outside of the realm of traditional marriage in colonial America that Virginia amended its anti-miscegenation law in 1691 to banish from the community any white person who married a “negro,” “mulatto” or Indian. (Wallenstein, supra, at 15-16). Couched in “the language of hysteria rather than legalese,” the avowed purpose of Virginia’s 1691 law was to prevent “that abominable mixture and spurious issue” of whites with blacks or Indians. (Id. at 15).

Although the first American anti-miscegenation laws were enacted in the Chesapeake Bay colonies, they quickly spread throughout the country. Massachusetts enacted an anti-miscegenation law in 1705. (Carter G. Woodson, The Beginnings of Miscegenation of the Whites and Blacks, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law 42, 45, 49 [Werner Sollors ed., 2000], annexed to the Appendix as Tab C). Pennsylvania passed its anti-miscegenation law in 1725, and Delaware enacted a similar law in 1726. (Charles Frank Robinson II, Dangerous Liaisons: Sex & Love in the Segregated South 4 [2003], annexed to the Appendix as Tab D).

By the time of the Civil War, laws prohibiting interracial marriage covered most of the South and much of the Midwest, and they were beginning to appear in Western states. (See David H. Fowler, Northern Attitudes Toward Interracial Marriage: Legislation & Public Opinion in the Middle Atlantic & the States of the Old Northwest, 1780-1930 214-219 [1987], annexed to the Appendix as Tab E). The proponents of these laws argued that they were necessary to uphold the law of nature:

“Hybridism is heinous. Impurity of races is against the law of nature. Mulattoes are monsters. The law of nature is the law of God. The same law which forbids consanguineous amalgamation; forbids ethnical amalgamation. Both are incestuous. Amalgamation is incest.”

(Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical & Practical 239-240 [1854], annexed to the Appendix as Tab F).

Although New York State never enacted an anti-miscegenation law, interracial relations were still subject to strong taboo here and vilified in the political arena. Indeed, the term “miscegenation” was first used in an anonymous propaganda pamphlet printed in New York City in 1863. The term was coined from two Latin words meaning “to mix” and “race.” The pamphlet – falsely attributed to the Republican Party and abolitionists — advocated the “interbreeding” of the white and black races so that they would become indistinguishably mixed. The pamphlet was later exposed as a “dirty trick” instigated by Democrats to discredit Republicans. (See e.g. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Miscegenation <en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miscegenation> [last accessed August 3, 2005]; The Miscegenation Hoax <www.museumofhoaxes.com/ miscegenation.html> [last accessed August 3, 2005]).

During Reconstruction, southern Democrats adopted the New York-minted term “miscegenation” and insisted on the necessity of preserving the sanctity of marriage by banning interracial marriage. (See Moran, supra, at 26). A few southern states repealed their anti-miscegenation laws during Reconstruction, but societal pressure to spurn interracial relationships remained steadfast. (Id.). When white southern males regained control of their state legislatures after Reconstruction, they promptly reinstated anti-miscegenation laws. (See id. at 27).

Nor did ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and its guarantee of equal protection bring any change in the courts’ view of the constitutionality of these laws. Over the next century, scores of courts confronted challenges to these racial restrictions and (with only two exceptions) consistently upheld the laws on the basis of longstanding tradition, “equal” application to the races and the “logic” of prohibiting interracial marriage. For example, in 1878, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia stated:

“The public policy of this state, in preventing the intercommingling of the races by refusing to legitimate marriages between them has been illustrated by its legislature for more than a century…. The purity of public morals, the moral and physical development of both races, and the highest advancement of our cherished southern civilization … all require that they should be kept distinct and separate, and that connections and alliances so unnatural that God and nature seem to forbid them, should be prohibited by positive law, and be subject to no evasion.”

(Kinney v Virginia, 71 Va 858, 869 [1878]; see e.g. Dodson v Arkansas, 61 Ark 57, 60-61, 31 SW 977, 977-978 [1895] (anti-miscegenation law held not unconstitutional or even “affected” by amendments to Federal Constitution); Missouri v Jackson, 80 Mo 175, 177 [1883] (traditional anti-miscegenation law held not to be discriminatory and violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution as it applies equally to the races); Green v Alabama, 58 Ala 190, 195-197 [1877] (same); Lonas v Tennessee, 50 Tenn 287, 312 [1871] (holding anti-miscegenation law unaffected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution); Indiana v Gibson, 36 Ind 389, 393-394 [1871] (same); Scott v Georgia, 39 Ga 321, 323, 327 [1869] (upholding constitutionality of anti-miscegenation law and stating that “the offspring of these unnatural connections are generally sickly and effeminate”)).

Despite the proliferation of anti-miscegenation laws, opponents of interracial marriage feared that state laws were insufficient to protect the sanctity of marriage. In December 1912, Representative Seaborn Roddenberry of Georgia proposed to amend to the United States Constitution to declare “Intermarriage between Negroes or persons of color and Caucasians … is forever prohibited.” (49 Cong Rec 502 [Dec. 11, 1912]). Leaders from around the country denounced interracial marriage. For example, Governor William Mann of Virginia called miscegenation ‘“a desecration of one of our sacred rites.’” Even New York’s Governor John Dix called it “‘a blot on our civilization’” and ‘“a desecration of the marriage tie [that] should never be allowed.’” (See Robinson, supra, at 79; see also Denise C. Morgan, Jack Johnson: Reluctant Hero of the Black Community, 32 Akron L Rev 529, 548 [1999]).

B Marriage Prohibitions Extended To Numerous Racial Groups

Although the first anti-miscegenation laws targeted whites and blacks, many states expanded their application to other racial groups. (See Peggy Pascoe, Miscegenation Law, Court Cases & Ideologies of “Race” in Twentieth Century America, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law 178, 183 [Werner Sollors ed., 2000], annexed to the Appendix as Tab G). Twelve states prohibited marriage between whites and Native Americans. (Id.). After the mid-eighteenth century, when people from the Far East began to immigrate to the United States, states with substantial populations of Chinese and Japanese responded by enacting anti-miscegenation laws prohibiting marriage between whites and “Mongolians.” (Moran, supra, at 28-36).

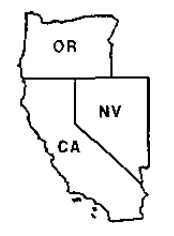

As new “nonwhite” immigrant communities formed, states amended their anti-miscegenation laws to prevent marriages between whites and these immigrants. (Id. at 31-32). In 1862, Oregon passed its first anti-miscegenation law. (See 1862 Or Laws § 63-102). In 1866, Oregon amended the statute to prohibit marriage between “any white person, male or female” and “any negro, Chinese, or any person having one fourth or more negro, Chinese, or Kanaka [Native Hawaiian] blood, or any person having more than one-half Indian blood.” (See 1866 Or Laws § 23-1010).

In 1850, California enacted a law prohibiting marriages between “white persons” and “negroes or mulattoes.” (Leti Volpp, American Mestizo: Filipinos & Anti-Miscegenation Laws in California, in Mixed Race America & the Law: A Reader 86 [Kevin R. Johnson ed., 2003], annexed to the Appendix as Tab H). Then, in 1878, California amended its constitution to restrict the intermarriage of whites and Chinese. (See Moran, supra, at 31). Shortly thereafter, the California Legislature amended the Civil Code to ban the union of “‘a white person with a negro, mulatto, or Mongolian.’” (Id. [citation omitted]). Later, it amended the law to include “‘members of the Malay race’” as well. (See id. at 38 [citation omitted]).

The specific targets of anti-miscegenation laws varied from state to state, as different racial or national groups were singled out by specific statutes reflecting legislative bigotry directed at particular racial groups. (Randall Kennedy, Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity & Adoption 220 [2003], annexed to the Appendix as Tab I). Other states enforced their anti-miscegenation policies on the basis of judicial decisions that turned on white/non-white distinctions. For example, Virginia voided a marriage between a white person and a person of Chinese descent on the basis of that state’s statute making it “unlawful for any white person in this State to marry any save a white person, or a person with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian.” (See Naim v Naim, 197 Va 80, 81, 87 SE2d 749, 750 [citation omitted], vacated and remanded 350 US 891 [1955], adhered to 197 Va 734, 90 SE2d 849 [1956]). All told, thirty- eight states had anti-miscegenation laws in effect at one time or another. (See Wallenstein, supra, at 253-254). By the end of World War II, thirty states still had such statutes. (See id. at fig. 8).

State anti-miscegenation laws were considered constitutional until 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down such discrimination as an unconstitutional interference with an individual’s fundamental right to marry. (Loving, 388 US at 12; see also Naim, 197 Va at 81, 87 SE2d at 750; Kinney, 71 Va at 869; Dodson, 61 Ark at 60-61, 31 SW at 977-978 (anti-miscegenation law held not unconstitutional or even “affected” by amendments to Federal Constitution); Jackson, 80 Mo at 177 (traditional anti-miscegenation law held not to be discriminatory and violative of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution as it applies equally to the races); Green, 58 Ala at 195-197 (same); Lonas, 50 Tenn at 312 (holding anti-miscegenation law unaffected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution); Gibson, 36 Ind at 393-394 (same); Scott, 39 Ga at 323, 327 (upholding constitutionality of anti-miscegenation law and stating that “the offspring of these unnatural connections are generally sickly and effeminate”).

Anti-Miscegenation Laws Enjoyed Vast Popular Support

Bans on interracial marriage reflected contemporary public sentiment. In 1958, a Gallup Poll indicated that 96 percent of all Americans opposed interracial marriage. (See Nicholas D. Kristof, Marriage: Mix and Match, NY Times, Mar. 3, 2004, at A23). In 1972—five years after the Supreme Court declared bans on interracial marriage unconstitutional—a Gallup Poll reported that 75 percent of all white Americans still opposed interracial marriage. (See Charlotte Astor, Gallup Poll: Progress in Black/White Relations, But Race is Still an Issue <usinfo.state.gov/ joumals/itsv/ 0897/ijse/gallup.htm> [last accessed August 3, 2005]). In 2000, Alabama became the last state to repeal its anti-miscegenation law, with 40 percent of its electorate voting to keep the prohibition on the books. (TheFreeDictionary.com, Miscegenation <www.encyclopedia.thefreedictionary. com/miscegenation> [last accessed August 3,2005]).

THE CITY’S ARGUMENTS ATTEMPTING TO CIRCUMSCRIBE THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO

MARRY DO NOT WITHSTAND SCRUTINY

The decision below should be affirmed. Amici urge this Court to keep in mind the history described above in determining whether New York’s prohibition on marriages between individuals of the same sex violates the New York State Constitution. The City argues that the government has the power to deny same-sex couples the right to enter into civil marriages by defining the right too narrowly and by suggesting that the recognition of that right must somehow become more “popular” before it is accepted. Taking a cue from the “reasoning” employed by the opponents of interracial marriage before Loving, the City also suggests that denying same-sex couples the right to enter into civil marriage is not discriminatory because it is “equally” applied. This Court should reject those narrow and misleading arguments.

Contemporary “Popular Opinion” Does Not Define The Fundamental Right To Be Free From Unwarranted Governmental Intrusion

All parties to this case agree that the right to marry is a constitutionally protected fundamental right. The reason that individuals have a fundamental right to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion in decisions involving marriage is that the decision to marry is fundamentally personal and private in nature. (See Griswold v Connecticut, 381 US 479, 486 [1965] (“We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights”)). Marriage is among those matters “involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, [which] are central to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.” (Planned Parenthood v Casey of Southeastern Pa., 505 US 833, 851 [1992]).

Although the parties agree that there is a fundamental right to marry, they disagree about the scope of this right. Respondents and Amici view the right as the right of one individual to enter into a marriage with another individual of his or her choice. The City argues that the right at issue is limited to the right to enter into a marriage with a member of the opposite sex. The City claims that Respondents are seeking a new right to “same-sex marriage” that has never before existed. This narrow interpretation of the right to marry finds no support in constitutional jurisprudence and is inconsistent with decisions striking down anti-miscegenation statutes.

The City has advanced three overlapping arguments in this area to restrict Respondents’ rights in this case. First, it claims that courts should always define fundamental rights as narrowly as possible. Second, it claims that a right is fundamental only if (and to the extent that) it has been exercised and protected throughout our nation’s history. Third, the City essentially claims that a right is fundamental only if its exercise is generally accepted in our society. Amid respond to each point in turn.

Fundamental Rights Should Not Be Defined Narrowly to Incorporate the Challenged Governmental Restriction

The City argues that fundamental rights must be defined narrowly, framing the issue in this case as whether there is a fundamental right to same-sex marriage. This view contradicts a long line of constitutional law and, in particular, cases involving anti-miscegenation statutes.

Challenges to claimed violations of fundamental rights require a two- step analysis: (1) Does the statute at issue restrict or burden the exercise of a fundamental right? If so, (2) is the restriction or burden narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest? (See e.g. Hernandez, 7 Misc 3d at 479-480; Zablocki v Redhail, 434 US 374, 388 [1978]).

The New York Constitution does not contain any of the constraints urged by the City to “narrow” the liberty of New York citizens. Article I, § 11 of the New York State Constitution provides, in pertinent part, that “[n]o person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws of this state or any subdivision thereof.” (NY Const, art I, § 11). And Article I, § 6 of the New York State Constitution provides, in pertinent part, that “[n]o person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” (NY Const, art I, § 6).

The right to liberty necessarily includes the right to be free from unjustified government interference in one’s privacy. (See People v Onofre, 51 NY2d 476, 486-489 [1980], cert denied 451 US 987 [1981]). Thus, the analysis of Respondents’ due process claim begins with the question whether the right to marriage is a fundamental right entitled to due process protection, both as a general liberty right and as a specific privacy right. Amici submit that it is both. Here, the City tries to avoid this analytical framework by incorporating the challenged form of bigotry itself into the definition of the “right.” This technique of “creative definition” was also employed by the opponents of interracial marriage until its fallacy was exposed nearly forty years ago.

Furthermore, the City’s argument should wither here, given that the whole purpose of the New York State Constitution is to secure people’s freedom. Indeed, the Preamble of the New York State Constitution proclaims “[w]e, the People of the State of New York, grateful to Almighty God for our [f]reedom, in order to secure its blessings, do establish this Constitution.” (NY Const, Preamble). And, to quote the 1992 Supreme Court of Kentucky decision in Kentucky v Wasson (842 SW2d 487 [Ky 1992]), which struck down Kentucky’s anti-sodomy laws:

“[g]iven the nature, the purpose, the promise of our Constitution, and its institution of a government charged as the conservator of individual freedom, I suggest that the appropriate question is not ‘[w]hence comes the right to privacy?’ but rather, ‘[w]hence comes the right to deny it?”’

(Id. at 503 [Combs, J., concurring]).

The New York Court of Appeals has expressed its willingness to uphold our state’s Constitutional protections when individual liberties and fundamental rights are at issue. (See People v Harris, 77 NY2d 434, 437-438 [1991] (“Our federalist system of government necessarily provides a double source of protection and State courts, when asked to do so, are bound to apply their own Constitutions notwithstanding the holdings of the United States Supreme Court…. Sufficient reasons appearing, a State court may adopt a different construction of a similar State provision unconstrained by a contrary Supreme Court interpretation of the Federal counterpart”) [citation omitted]).

A review of cases in which the U.S. Supreme Court has found government intrusion on fundamental rights in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause reveals that, in determining the existence of a fundamental right, the Court considers the nature of the right at issue rather than some very specific governmental restriction being challenged. For example, in Meyer v Nebraska (262 US 390, 401-403 [1923]), and in Pierce v Society of Sisters of Holy Names of Jesus & Mary (268 US 510, 534-535 [1925]), the Court considered whether parents had a right to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion in decisions about how to educate their children. The Court did not frame the issue as whether there was a fundamental right for children to learn the German language or whether there was a fundamental right to attend a private school. In Skinner (316 US at 541), the Court considered whether there was a fundamental right to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion in decisions about whether to have offspring, not whether a convicted criminal had the fundamental right to bear children. In Zablocki (434 US at 384-385, 388), and Turner v Safley (482 US 78, 95-96 [1987]), the Court considered whether there was a fundamental right to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion in decisions to marry, not whether deadbeat dads or prison inmates in particular had a specific right to marry. Most recently, in Lawrence v Texas (539 US 558, 578 [2003]), the Court considered whether there is a fundamental right to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters of private, consensual sexual conduct, not whether there is a specific right to engage in homosexual sodomy. The very notion of “fundamental” rights reserved to all people naturally flows from the nature of a written constitution that defines the limited power of the State. That notion reflects the view that people are beings possessed of personal dignity and human worth. States exist to preserve that dignity, worth and autonomy. Only totalitarian regimes view themselves as “dispensing” rights to people at the whim of a transitory majority or the favor of a particular faction.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s rejection of anti-miscegenation statutes exposes the fallacy of the City’s argument in this case. In Loving (388 US at 12), the Supreme Court did not ask whether there was a specific right to enter into an interracial marriage. Instead, the Court asked more generally whether there was a fundamental and general right to be free from unwarranted governmental interference in decisions regarding marriage. After answering that question affirmatively, the Court considered whether the prohibition on interracial marriage was narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest and, of course, concluded it was not.

Significantly, the Supreme Court has since emphasized the broad basis of its decision in Loving. The Court has explained that its decision in Loving “could have rested solely on the ground that the statutes discriminated on the basis of race in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. . . . But the Court went on to hold that the laws arbitrarily deprived the couple of a fundamental liberty protected by the Due Process Clause, the freedom to marry.” (Zablocki, 434 US at 383 [citation omitted]). The California Supreme Court took a similarly broad perspective when it struck down an anti-miscegenation statute almost twenty years before Loving. Justice Traynor wrote:

“[Marriage] is a fundamental right of free men. There can be no prohibition of marriage except for an important social objective and by reasonable means…. Since the right to marry is the right to join in marriage with the person of one’s choice, a statute that prohibits an individual from marrying a member of a race other than his own restricts the scope of his choice and thereby restricts his right to marry.”

(Perez v Lippold, 32 Cal 2d 711, 715, 198 P2d 17, 19 [1948]).

And there is substantial New York Court of Appeals precedent speaking to the breadth of the fundamental right to marry under New York Law. As Justice Ling-Cohan explained in the decision below:

“New York courts have analyzed the liberty interest at issue in terms that recognize and embrace the broader principles at stake…. Indeed, as the Court of Appeals has consistently made clear, ‘[A]mong the decisions protected by the right to privacy, are those relating to marriage.’ ([Doe v Coughlin, 71 NY2d 48, 52 [1987], cert. denied 488 US 879 [1988]]; see also [People v Shepard, 50 NY2d 640, 644 [1980]] (noting courts’ willingness ‘to strike down State legislation which invaded the “zone of privacy” surrounding the marriage relationship’) [citation omitted]; [Levin v Yeshiva Univ., 96 NY2d 484, 500 [2001, Smith, J., concurring]] (‘[M]arriage is a fundamental constitutional right’); [Mary of Oakknoll v Coughlin, 101 AD2d 931, 932 [3d Dept 1984]] (‘[T]he right to marry is one of fundamental dimension’)).”

(7 Misc 3d at 477-478).

The City’s Focus on the Historical Recognition of the Right to Marry Is Overly Narrow

The City argues that the right to marry must be narrowly viewed to include only opposite-sex marriages because fundamental rights are deeply grounded in our nation’s history. This argument is contrary to constitutional jurisprudence and decisions striking down anti-miscegenation statutes because “deeply grounded” bigotry can never justify contemporary discrimination.

While the determination of a fundamental right looks to history and the ordered concept of liberty, the City can cite no New York case that requires tying the definition of a fundamental right to the state’s “traditional” definition thereof. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that any form of discrimination can be styled as permissible merely because it has been “traditionally pervasive.” The United States Supreme Court has never held that it will solely rely on history when evaluating a constraint on fundamental rights. In Casey, the Supreme Court stated:

“[S]uch a view would be inconsistent with our law. It is a promise of the Constitution that there is a real`m of personal liberty which the government may not enter. We have vindicated this principle before. Marriage is mentioned nowhere in the Bill of Rights and interracial marriage was illegal in most States in the 19th century, but the Court was no doubt correct in finding it to be an aspect of liberty protected against state interference by the substantive component of the Due Process Clause. . . .”

(505 US at 847-848).

Thus, the Supreme Court’s analysis of fundamental rights is grounded in our Nation’s historical tradition of protecting uniquely personal and intimate decisions from unjustified government intrusion, not in the history of a specific act or decision. “If the question whether a particular act or choice is protected as a fundamental right were answered only with reference to the past, liberty would be a prisoner of history.” (Note, Litigating the Defense of Marriage Act: The Next Battleground for Same-Sex Marriage, 117 Harv L Rev 2684, 2689 [2004]).

“Clearly, the right to choose one’s life partner is quintessentially the kind of decision which our culture recognizes as personal and important. . . . The relevant question is not whether same-sex marriage is so rooted in our traditions that it is a fundamental right, but whether the freedom to choose one’s own life partner is so rooted in our traditions.”

(Brause v Bureau of Vital Statistics, No. 3AN-95-6562 CI, 1998 WL 88743, *4 [Alaska Super Ct Feb. 27, 1998], aff’d sub nom Brause v Alaska Dept. of Health & Soc. Servs., 21 P3d 357 [Alaska 2001]).

The history of interracial marriages exposes the fallacy of the City’s argument: It was once argued that there is no fundamental right to marry someone of a different race because such marriages had a long history of being prohibited. (See e.g. Lonas, 50 Term at 293-295; Britell v Jorgensen (In re Takahashi’s Estate), 113 Mont 490, 493-494, 129 P2d 217, 219 [1942]; Perez, 32 Cal 2d at 747, 198 P2d at 38 [Shenk, J., dissenting] (arguing that the prohibition of interracial marriage had a long history and twenty-nine states continued to have such laws)). In 1948, when the California Supreme Court struck down California’s anti-miscegenation statute, Justice Carter acknowledged that “[t]he freedom to marry the person of one’s choice has not always existed” but nonetheless concluded that the right was fundamental and that anti-miscegenation statutes impermissibly violated that right. (Perez, 32 Cal 2d at 734-735, 198 P2d at 31 [Carter, J., concurring]).

In Loving, the Supreme Court recognized an individual’s fundamental right to be free from governmental intrusion in marriage not because interracial marriage was permitted at common law, but because the Constitution required it. (388 US at 12). Likewise, in Perez, the California Supreme Court recognized each individual’s fundamental right “to join in marriage with the person of one’s choice,” despite the many historical restrictions imposed upon the exercise of that right. (32 Cal 2d at 717,198 P2d at 21).

Additionally, as set forth above, until 1967, this Nation had a long and deep-seated history of prohibiting and disapproving of interracial marriages. The statutes were routinely defended as having “been in effect in this country since before our national independence.” (Perez, 32 Cal 2d at 742, 198 P2d at 35 [Shenk, J. dissenting]). Indeed, anti-miscegenation laws were the most deeply embedded form of legal race discrimination in our nation’s history—lasting over three centuries. (Peggy Pascoe, Why the Ugly Rhetoric Against Gay Marriage is Familiar to This Historian of Miscegenation [2004] <hnn.us/articles/4708.html> [last accessed August 3, 2005]).

The City also suggests that there is no right to marry someone of the same sex because prohibitions on such marriages are still nearly universal in the United States. According to this theory, anti-miscegenation statutes should have remained constitutional as long as they remained prevalent. Such an argument is both historically and legally wrong.

As an initial matter, the sheer prevalence of a law does not determine its constitutionality. For example, Lawrence (539 US at 577-578) quoted from Justice Stevens’s dissent in Bowers v Hardwick, 478 US 186, 216 [1986] —

“‘the fact that the governing majority in a State has traditionally viewed a particular practice as immoral is not a sufficient reason for upholding a law prohibiting the practice.’”

Moreover, disapproval of interracial marriage was also once commonplace. When anti-miscegenation statutes were challenged, states relied upon their prevalence and acceptance to defend them. (E.g. Henkle v Paquet (In re Paquet’s Estate), 101 Or 393, 399, 200 P 911, 913 [1921] (miscegenation statutes “‘have been universally upheld as a proper exercise of the power of each state to control its own citizens’”) [citation omitted]; Kirby v Kirby, 24 Ariz 9, 11, 206 P 405, 406 [1922]; Lee v Giraudo (In re Monks’ Estate), 48 Cal App 2d 603, 612, 120 P2d 167, 173 [Ct App 1941], appeal dismissed 317 US 590 [1942]). Prohibitions on interracial marriage remained commonplace at the time those prohibitions were invalidated. As set forth above, when the California Supreme Court struck down an anti-miscegenation statute in 1948, thirty states had similar statutes. And when the Supreme Court struck down anti-miscegenation statutes in Loving, sixteen states still had similar statutes, and 75 percent of white Americans still opposed interracial marriage. (See Astor, supra).

More importantly, prohibitions on interracial marriage did not become unconstitutional because they were found in fewer states; the laws were always contrary to constitutional principles. (Perez, 32 Cal 2d at 736, 198 P2d at 32 [Carter, J., concurring] (“the statutes now before us never were constitutional”)). The fact that only sixteen states had such laws in 1967 may have made the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving less controversial, but the Court’s long- overdue decision was not based on the number of states having anti-miscegenation laws at the time.

Like the prohibitions on interracial marriage, prohibitions on the right of same-sex couples to enter into civil marriage cannot withstand serious constitutional scrutiny based on mere repetition of the claim that there is no fundamental right to “same-sex marriage” or because many states and members of the public continue to support such prohibitions.

In addition to burdening a fundamental right, prohibitions on marriages between individuals of the same sex are discriminatory. Some argue that the prohibition does not discriminate because it applies equally to men and women. Claims of “equal treatment” were also made to justify prohibitions on interracial marriage. An examination of those claims and the cases that ultimately rejected those “justifications” should inform this case.

Defenders of anti-miscegenation statutes repeatedly argued that the statutes did not discriminate because they applied equally to both black and white people:

“[The prohibition] was not then aimed especially against the blacks…. They have the same right to make and enforce contracts with whites that whites have with them, but no rights as to the white race which the white race is denied as to the black. The same rights to contract with each other that the whites have with each other; the same to contract with the whites that the whites have with blacks…”

(Lonas, 50 Tenn at 298-299). In 1877, the Alabama Supreme Court relied upon a similar rationale:

“[I]t is for the peace and happiness of the black race, as well as of the white, that such laws should exist. And surely there can not be any tyranny or injustice in requiring both alike, to form this union with those of their own race only, whom God hath joined together by indelible peculiarities, which declare that He has made the two races distinct.”

(Green, 58 Ala at 195). The City’s argument here echoes the 1883 words of the Missouri Supreme Court holding that “[t]he act in question is not open to the objection that it discriminates against the colored race, because it equally forbids white persons from intermarrying with negroes, and prescribes the same punishment for violations of its provisions by white as by colored persons…” (Jackson, 80 Mo at 177). Likewise, in 1921, the Supreme Court of Oregon upheld a ban on marriages between Native Americans and whites, stating simply that “the statute does not discriminate. It applies alike to all persons….” (In re Paquet’s Estate, 101 Or at 399, 200 P at 913). And, in 1942, the Supreme Court of Colorado stated: “There is here no question of race discrimination. The statute applies to both white and black.” (Jackson v City & Cty of Denver, 109 Colo 196, 199, 124 P2d 240, 241 [1942]).

In 1948, the California Supreme Court finally rejected this unthinking mantra, explaining the fallacy of “equal application”:

“It has been said that a statute such as section 60 does not discriminate against any racial group, since it applies alike to all persons whether Caucasian, Negro, or members of any other race. . . . The decisive question, however, is not whether different races, each considered as a group, are equally treated. The right to marry is the right of individuals, not of racial groups. The equal protection clause of the United States Constitution does not refer to rights of the Negro race, the Caucasian race, or any other race, but to the rights of individuals.”

(Perez, 32 Cal 2d at 716, 198 P2d at 20 [emphasis added; citation omitted]). Thus, the proper analysis of the issue focuses on the individual. Because a black individual was not permitted to marry an individual whom a white individual could marry, the anti-miscegenation statute was found to discriminate on the basis of race. Similarly, the statute discriminated on the basis of race because a white individual could not marry an individual whom a black individual could marry.

Almost twenty years later, the United States Supreme Court reached the same conclusion: “[W]e reject the notion that the mere ‘equal application’ of a statute containing racial classifications is enough to remove the classifications from the Fourteenth Amendment’s proscription….” (Loving, 388 US at 8; see also McLaughlin v Florida, 379 US 184, 191 [1964] (“Judicial inquiry under the Equal Protection Clause, therefore, does not end with a showing of equal application among the members of the class defined by the legislation”)). For the same reason, any simplistic “equal application” argument must fail, as its rhetorical appeal is matched only by its logical weakness. Accordingly, the decision below should be affirmed.

For the reasons set forth above, NYCLA, NBJC and MBBA, as amici curiae, respectfully request this Court to affirm Justice Doris Ling-Cohan’s decision in the court below rejecting New York’s prohibition on marriage between same-sex partners as unconstitutional.

Dated: New York, New York

August 3, 2005

By: Norman L. Reimer

President

14 Vesey Street

New York, NY 10007

(ph) 212-267-6646

(fax) 212-406-9252

(e-mail) nreimer@gfrglawfirm.com

National Black Justice Coalition, Amicus Curiae

Washington National Office

17251 Street, NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20006

Att.: H. Alexander Robinson

Executive Director/CEO

(ph) 202-349-3755

(fax) 202-349-3757

(e-mail) arobinson@nbjcoalition.org

Metropolitan Black Bar Association, Amicus Curiae

299 Broadway, Suite 1203A

New York, NY 10007

Att: Nadine C. Johnson, President

Cornett L. Lewers, Chairman

(ph) 212-964-1645

(e-mail) president@mbbany.org

Of Counsel:

Ivan J. Dominguez

Kathryn Shreeves

Jean M. Swieca

This computer generated brief was prepared using a proportionally spaced/monospaced typeface using Microsoft Word 2000 (in Windows XP environment).

|

Name of typeface: Point size: Line spacing: |

Times New Roman 14 pt. Double |

The total number of words in the brief, inclusive of point headings and footnotes, and exclusive of pages containing the table of contents, table of authorities, proof of service, certificate of compliance, or any authorized addendum is 7771.

Dated: August 3,2005

Supreme Court Of The State Of New York

Appellate Division – First Department

Daniel Hernandez and Nevin Cohen,

Lauren Abrams and Donna Freeman-Tweed,

Michael Elsasser and Douglas Robinson,

Mary Jo Kennedy and Jo-Ann Shain,

and Daniel Reyes and Curtis Woolbright,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

-against-

Victor L. Robles, in his official capacity as

City Clerk of the City of New York,

Defendant-Appellant.

APPENDIX TO BRIF OF AMICI CURIAE

New York County Lawyers’ Association

14 Vesey Street

New York, NY 10007

212-267-6646

National Black Justice Coalition

17251 Street, NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20006

202-349-3755

Metropolitan Black Bar Association,

299 Broadway, Suite 1203A

New York, NY 10007

212-964-1645

OF Counsel:

|

Ivan J. Dominguez |

|

|

Kathryn Shreeves |

|

|

Jean M. Swieca |

Attorneys for Amici Curiae |

Reproduced on Recycled Paper

|

APPENDIX |

|

|

TAB |

|

|

Excerpts from Peter Wallenstein, Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage & Law—An American History [2002] |

A |

|

Excerpts from Rachel F. Moran, Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race & Romance [2001] |

B |

|

Excerpts from Carter G. Woodson, The Beginnings of Miscegenation of the Whites and Blacks, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

C |

|

Excerpts from Charles Frank Robinson II, Dangerous Liaisons: Sex & Love in the Segregated South [2003] |

D |

|

Excerpts from David H. Fowler, Northern Attitudes Toward Interracial Marriage: Legislation & Public Opinion in the Middle Atlantic & the States of the Old Northwest, 1780-1930 [1987] |

E |

|

Excerpts from Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical & Practical [1854] |

F |

|

Excerpts from Peggy Pascoe, Miscegenation Law, Court Cases & Ideologies of “Race” in Twentieth Century America, in Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature & Law [Werner Sollors ed., 2000] |

G |

|

Excerpts from Leti Volpp, American Mestizo: Filipinos & Anti-Miscegenation Laws in California, in Mixed Race America & the Law: A Reader [Kevin R. Johnson ed., 2003] |

H |

|

Excerpts from Randall Kennedy, Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity & Adoption [2003] |

I |

Race, Marriage, and Law—An American History

Peter Wallenstein

“Indian Foremothers” by Peter “Wallenstein, from The Devil’s Lane: Sex and Race in the Early South, edited by Catherine Clinton and Michele Gillespie, (c) 1996 by Catherine Clinton and Michele Gillespie. Used by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc.

TELL THE COURT I LOVE MY WIFE

Copyright (c) Peter Wallenstein, 2002.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

First published in hardcover in 2002 by Palgrave Macmillan

First PALGRAVE MACMILLAN(un) paperback edition: January 2004

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS.

Companies and representatives throughout the world.

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan(r) is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries.

ISBN 1-4039-6408-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallenstein, Peter.

Tell the court I love my wife : race, marriage, and law: an American history / by Peter Wallenstein.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 1-4039-6408-4

1. Interracial marriage—Law and legislation—United States—History. I. Title.

KF511.W35 2002

346.7301’6-dc21

2002072510

A catalogue record for this book is available fiom the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre

First PALGRAVE MACMILLAN paperback edition: January 2004

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

For my miracle,

Sookhan

Sex, Marriage, Race, and Freedom in the Early Chesapeake

“For prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue which hereafter may encrease in this dominion, as well by negroes, mulattoes, and Indians intermarrying with English, or other white woman, as by their unlawfull accompanying with one another”

—Law of Virginia (1691)

No wedding photos, no baby pictures, commemorate the events. John Rolfe and Pocahontas married in 1614, and their son Thomas was born in 1615, when the English colony that was planted in 1607 at Jamestown, Virginia, was still very new. Multiracial Virginians originated as early as that time, and many people—sojourners and residents, English and Native Americans alike—welcomed the interracial marriage that enhanced the likelihood of peace in the Chesapeake region of North America.1

No law at that time specifically governed interracial sex, interracial marriage, or multiracial children. Law or no law, few whites married Native Americans in colonial Virginia, so the union of John Rolfe and Pocahontas proved a notable exception. Restrictive laws, when they emerged, reflected lawmakers’ overriding concerns regarding Virginians of African ancestry, but they affected people in all other groups, too. At about the same time that Virginia began to legislate on the identity and status of mixed-race people, Maryland did as well.

When slavery supplanted servitude in supplying a labor force for the Chesapeake colonies, more African Americans lived in Virginia and Maryland combined than in all the other British North American colonies put together. For some years after the American Revolution, the two states on the Chesapeake Bay continued to contain a majority of all people with African ancestry living in the new nation. Thus the Chesapeake region generated the dominant experience of black and multiracial people in the settler societies of British North America and the early American republic.

Race, sex, slavery, and freedom commingled with society, economics, politics, and law in Virginia and Maryland in various and changing ways. In 1607—just before men on three ships from England made their way up what they named the James River, arrived at a place they called Jamestown, and established a colony there—the many residents of the Chesapeake region were all Native Americans. Over the next two centuries, newcomers and their progeny from both Europe and Africa soared in numbers while Indians seemed to vanish.

If the patterns had been more simple than they were, it might be possible to speak as though everyone was either white or black, and as though all blacks were slaves, whether in 1750 or 1850. But such was not the case, and boundaries were not so clear. Some black residents were free; Indians refused to vanish; and many people in Maryland and Virginia were multiracial. Some mixed-race people, though born unfree, were designated to remain so only for specific (though lengthy) periods—18, 21, 30, or 31 years. Some people, moreover, though born into lifelong slavery, gained their freedom.

Within marriage or outside it, people of European origin had children with Native Americans or people of African ancestry. This chapter and the next explore each of those complicating features of the social landscape, emphasizing two groups, those descended from white mothers and black (or mixed-race) fathers and those claiming Indian foremothers. Both chapters focus on a region— where most Virginians lived, east of the Blue Ridge mountains—whose population, in the years between 1760 and 1860, was roughly half white and half nonwhite, half free and half slave. In many times and places, only a minority was white, yet only a minority was slave. Tilting the balance was a middle group of people who were considered free but not white. This chapter takes a fresh look at their origins. In particular, it offers a history of the beginnings of legal restrictions on marriage between colonists who were defined as white and people who were defined as nonwhite.

Like Mother, Like Child

Before a law of race could fully develop, definitions of racial categories had to be put in place. In seventeenth-century Virginia and Maryland, these took a while to develop, although some kind of line separating white from nonwhite was ever-present. When, for example, the Virginia House of Burgesses wanted to refer to people of various groups, Europeans might variously be termed “Christians,” “English,” and “English or other white” persons. Race or color, religion, language or nation of origin—any category might do. Other people tended to get lumped under such categories as “negroes, mulattoes, and other slaves”; “negroe slaves”; “Indians or negroes manumitted, or otherwise free”; and any “negroe, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free.”2

In 1662, Virginias colonial assembly first addressed the question of the status of the children of interracial couples. The question before the legislators was whether “children got by any Englishman upon a negro woman should be slave or ffree.” The new law supplied a formula: “all children borne in this country [shall be] held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.”3

According to the 1662 law, children would follow the status of their mothers. Slave women would have slave children, regardless of who the father was; if she were a slave, then any child she had, even with a white father, would be a slave. Free women, whether white or not, would have free children, again no matter who the father was; if the woman was free, her child—black, white, or mixed-race—would be free too. All depended on whether the woman—whatever her racial identity—was slave or free. The fathers identity did not matter, so neither could his race or his status. Moreover, the 1662 law assumed that the mixed-race child was born to a couple who were not married to each other—in many cases, a slave woman and the white man who owned her. It did not address the question of interracial marriage itself.

Marriage, Children, and the Racial Identity of the Father

A successor act in 1691 took on the matter of marriage. That year, the Virginia assembly took action against sexual relations between free whites and nonwhites, at least in certain circumstances, regardless of whether the couple were single or had married. As a rule, colonial governments and churches fostered marriages between adults, but—reflecting a widespread pattern in colonial America—the Virginia assembly was not necessarily going to do any such thing regarding interracial unions. Slaves could contract no marriages that the law recognized. Free people could, but, after 1691, white people were not free to marry across racial lines. Prior to this time, some white women had married nonwhite men; the assembly tried to curtail the practice, punish infractions, and contain the consequences.4

The 1691 act, couched in the language of hysteria rather than legalese, was designed “for prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue which hereafter may encrease in this dominion, as well by negroes, mulattoes, and Indians intermarrying with English, or other white woman, as by their un-lawfull accompanying with one another.” In the cultural world that these legislators inhabited, it was anathema for white women to have sexual relations with nonwhite men. For the relationship to be sanctified in marriage was no better—if anything, it was worse—than if the couple remained unwed.5

The 1691 statute targeted sexual relations between white women and black men (the “abominable mixture”) and the children of such relationships (the “spurious issue”). The first thing the new law did was to outlaw interracial marriage for white men and white women alike. Actually, it did not ban the marriage but, rather, mandated the banishment of the white party to any interracial marriage that occurred, if that person was free and thus owed labor to no planter: “Whatsoever English or other white man or women being free shall intermarry with a negroe, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free, shall within three months after such marriage be banished and removed from this dominion forever.”6 If the bride in the interracial couple was white, then she would vanish from Virginia, and her mixed-race child would be born and raised outside Virginia.

The law began by condemning all marriages between whites and nonwhites, but its main intent was to target white women who strayed across racial lines, whether they actually married nonwhite men or not. An occasional white woman, even though unmarried, would have a child whose father was “negro or mulatto” (here lawmakers did not include Indians). Concerned about that contingency, legislators targeted the white mothers of interracial children—“if any English woman being free shall have a bastard child by any negro or mulatto,” she must, within a month of the birth, pay a fine of 15 pounds sterling to the church wardens in her parish. Her crime, such as it was, entailed a sexual relationship with a nonwhite man—in particular, a relationship that resulted in a mixed-race child.7

If the white mother of a multiracial child was free but could not pay the fine, the church wardens were to auction off her services for five years. The penalty called for her to pay in either money or time, property or liberty. But if she was an indentured servant, the law did not mean to punish her owner by denying him her labor (and thus his property). If she was a servant and thus not the owner of her own labor at the time of the offense, her sale for five years would take place after she had completed her current indenture.

In view of the provision for banishment, few white Virginians involved in interracial marriages would still be in the colony when their children came along. But this addressed only the question of the children—the “spurious issue”—of white women who actually went through a wedding ceremony, whose relationship would have been, before 1691, lawful. What about children whose parents’ “accompanying with one another” was “unlawful”—that is, the couple was unmarried? Any “such bastard child,” mixed-race and born in Virginia, was to be taken by the wardens of the church in the parish where the child was born and “bound out as a servant untill he or she shall attaine the age of thirty yeares.”8

If the mother stayed in Virginia and retained her freedom, therefore, she lost her child, who would be bound out as a servant until the age of 30. As is evident from this act, mixed-race children troubled the Virginia assembly if their mothers were white, not if they were black. The old rule continued to operate for the mixed-race children of white fathers, but a new rule targeted the problem of mixed-race children of white mothers. The law said nothing, however, about the nonwhite father of a white womans child. It imposed no penalty of loss of labor or liberty, though it surely broke up any family there might have been. The father was important to the law because, regardless of whether he was free or slave, he was nonwhite and had fathered a child by a white woman. But the penalties were imposed on the woman and the child.

The status, slave or free, of the child of a white man and a black woman continued, under the 1662 law, to depend on the status of the mother. The 1691 legislature worried about other questions, and it devised a new rule to address them. The new rule meant that the fathers identity could be as important as the mother’s. By 1691, the central question regarding the status of a child in Virginia had to do with whether the mother was white or black as much as whether she was free or slave. Most black women were slaves, so most children of black women would be slaves, although nonslave, nonwhite mothers would still bear nonslave children. If the mother was white, the answer depended on the racial identity of the father.

The legislature had, as its primary object, seeing that white men retained exclusive sexual access to scarce white women. It also had, as a significant secondary object, propelling the mixed-race children of a white mother out of the privileged white category and into a racial category that carried fewer rights, and out of the group born free and into long-term servitude to a white person.9

Eighteenth-Century Amendments

Legislation in 1705 modified the 1691 statute in several significant ways. In framing an act “declaring who shall not bear office in this country” that excluded “any negro, mulatto, or Indian,” the Virginia legislature defined “mulatto”—for the purpose of “clearing up all manner of doubts” that might develop regarding “the construction of this act, or any other act”—as “the child, grand child, or great grand child, of a negro.”10 It thereby defined as “mulatto” any mixed-race Virginian with at least one-eighth African ancestry. The statute probably sufficed at the time to exclude virtually all Virginians with any traceable African ancestry. In 1705, only some 86 years after the arrival in 1619 of

WHAT MISCENATION IS

-AND-

WALLER & WILLEFTS Publishers,

NEW YORK.

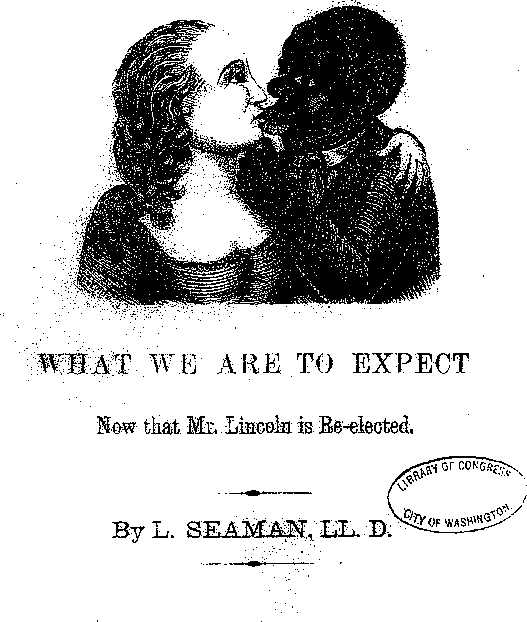

Figure 4. What Miscegenation Is! (1865). The word was widely adopted soon after its introduction in the 1864 presidential election year, and this pamphlet—its caricature of an African American man with a Caucasian woman reflecting, and designed to foster, fears of black men mixing with white women—came out soon after Abraham Lincoln was reelected. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

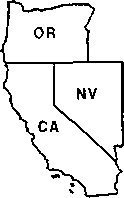

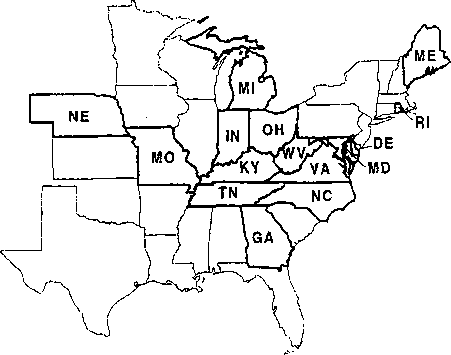

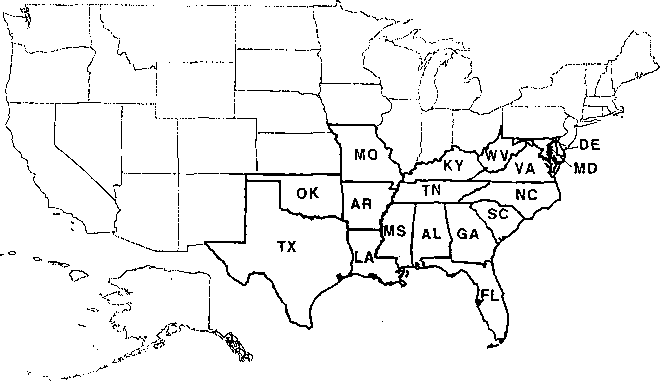

|

(left) Figure 5 Justice John Marshall Harlan was the U.S. Supreme Courts sole dissenter in The Civil Rights Cases (1883) and again in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), but in Pace v. Alabama (1883), also about the Fourteenth Amendment and “equal protection of the laws, ” he failed to dissent, so the Court unanimously upheld a miscegenation statute. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. (below) Figure 6. The South was solid in its allegiance to the antimiscegenation regime in 1866—one year after the Confederacy’s defeat in 1865 and one year before Congress passed the Reconstruction acts of1867. But many states outside the South also had such laws at that time. Some of the former Confederate states had just inaugurated such laws during the previous year; and seven—whether by legislative or judicial action—soon dropped their miscegenation laws for at least a few years. Produced by John Boyer, geography department, Virginia Tech. |

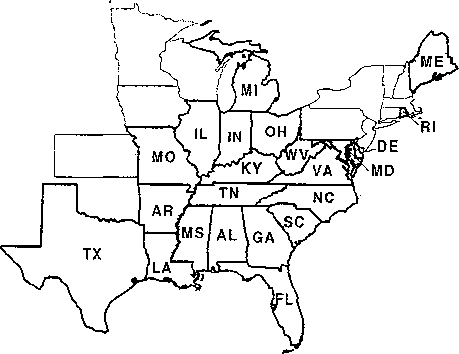

Figure 7. Of the 37 states in 1874, at least 9 (of 21) in the North and another 9 (of 16) in the South had miscegenation laws. Many western territories (hot shown here) also had such laws, but most states of the Lower South had lifted them. Produced by John Boyer, geography department, Virginia Tech.

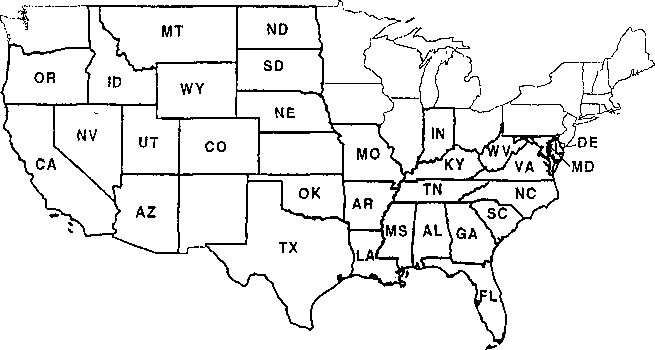

Figure 8. Between 1913 (when the last state enacted such a Law) and 1948 (when the California Supreme Court overturned that state’s law), the antimiscegenation regimes power was at its peak, and its territory held at 30 of the 48 states. Produced by John Boyer, geography department, Virginia Tech.

Figure 9. When the Lovings were arrested in 1958 in Virginia for their interracial marriage, 24 of the 48 states still had miscegenation laws on the book. Virginias law dated all the way back to 1691, Wyoming’s only to 1913. Produced by John Boyer, geography department, Virginia Tech.

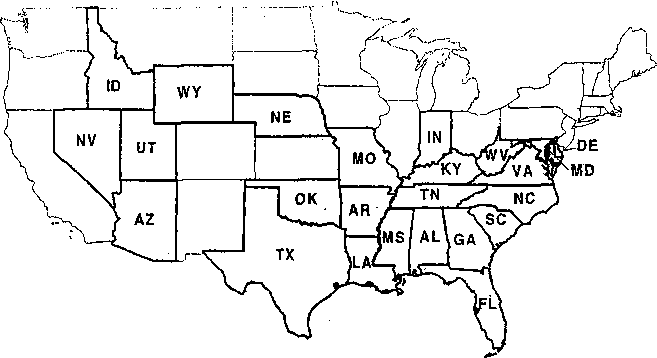

Figure 10. By 1966, the territory controlled by the antimiscegenation regime had shrunk to one-third of the nation—17 of the 50 states, clustered in the South. Into the 1960s, laws that banned interracial marriage continued to be enforced in those states. Produced by John Boyer, geography department, Virginia Tech.

Permanent Repeal of State

Miscegenation Laws, 1780–1967

The territory governed by the antimiscegenation regime kept changing. After beginning in the seventeenth century in the Chesapeake colonies, it spread north as well as south and then, in the nineteenth century, west to the Pacific. Over the years, some states peeled away from the regime, either temporarily or permanently. Suspensions of miscegenation laws took place in most of the Deep South during Reconstruction but proved temporary. With restoration there, and repeal in some northern states, the territory took on its twentieth-century contours, and was eventually—very briefly—restricted to the South.

As many as 12 states (or as few as 8) never had laws restricting interracial sex or marriage. Four of these were among the original 13 states: New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York (although New York, when it was New Amsterdam, a Dutch colony, had a law against interracial sex). Five other states never had such laws: Vermont, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, together with Hawaii and Alaska, both admitted in 1959. Three territories had such laws for a time but repealed them before statehood: Kansas (1859), New Mexico (1866), and Washington (1868); Wyoming did so, too (1882), but then it passed a new miscegenation law in 1913.

Between 1780 and 1887, 8 states (in addition to those 3 territories) permanently repealed their miscegenation laws (and 7 southern states abandoned the antimiscegenation regime for some years after 1867). Then, for many years, no states repealed such measures, while additional states inaugurated miscegenation laws as late as 1913, and 30 states (out of 48) retained those laws at the end of World War II. Repeal by 13 of the 30 by 1965 left 17 holdout states—Maryland (which repealed its law shortly before the Supreme Court handed down the decision in Loving v. Virginia, in June 1967) and 16 other states, from Delaware to Texas. The Loving decision brought an end to the enforceability of miscegenation laws in those remaining 16 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

A list of states with miscegenation laws follows, together with the years in which—through state action, between 1780 and the eve of the Loving decision in 1967—they permanently ended their participation in the antimiscegenation regime:1

|

Pennsylvania |

1780 |

|

Massachusetts |

1843 |

|

Iowa |

1851 |

|

Illinois |

1874 |

|

Rhode Island |

1881 |

|

Maine and Michigan |

1883 |

|