Have Questions? Contact Us.

Since its inception, NYCLA has been at the forefront of most legal debates in the country. We have provided legal education for more than 40 years.

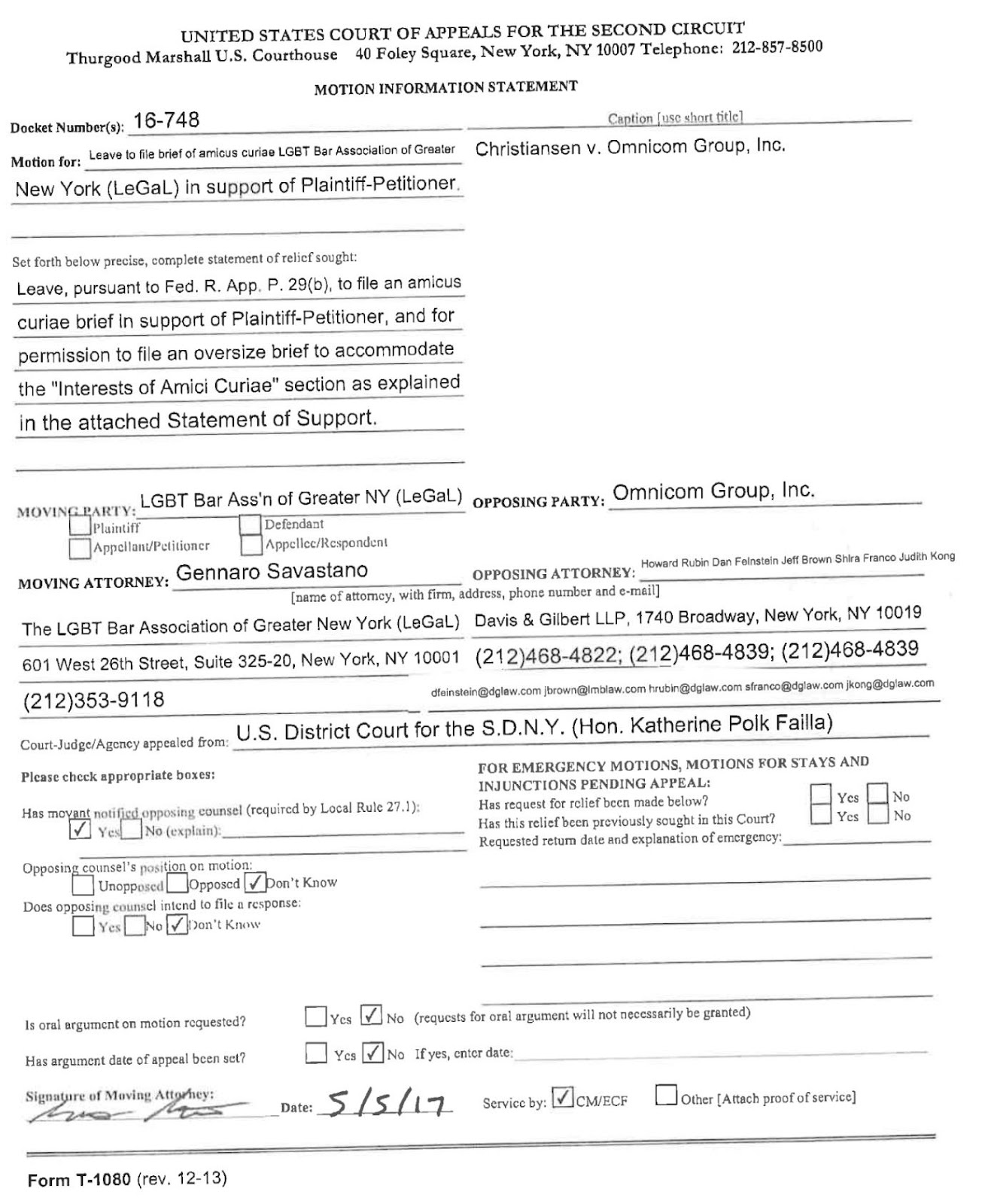

Case 16-748, Document 165, 05/05/2017, 2028017, Page1 of 29

SUPPORTING STATEMENT

Amicus curiae The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (LeGaL), author of the proposed brief, and the amici signatories are a coalition of voluntary bar associations and nonprofit organizations united in their commitment to protecting the rights of LGBT individuals and the prevention of workplace discrimination and harassment of all forms. Detailed statements of interests are attached.

LeGaL respectfully requests permission to file an oversized brief. In accordance with Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure 29 (b) and 32 (f), the brief contains 2,590 words, which is within the 2,600 word limit. However, the “Interests of Amici Curiae” (comprising six entities) is 669 words. LeGaL respectfully asks that this Court permission to submit an oversized brief accordingly.

The LGBT Bar Association

of Greater New York (LeGaL)

601 West 26th Street, Suite 325-20

New York, NY 10001

(212)353-9118

By: Gennaro Savastano

President

Amicus Curiae

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (“LeGaL”) was one of the nation’s first bar associations of the LGBT legal community and remains one of the largest and most active organizations of its kind in the country. Serving the New York metropolitan area, LeGaL is dedicated to improving the administration of the law, ensuring full equality for members of the LGBT community, and promoting the expertise and advancement of LGBT legal professionals. LeGaL, whose membership includes attorneys that regularly represent LGBT employees in cases of employment discrimination, has a fundamental interest in ensuring that Title VII’s protections extend to all LGBT employees.

The New York City Bar Association (the “City Bar”) is a voluntary association of over 24,000 member lawyers and law students. Among other initiatives, the City Bar addresses unmet legal needs, especially the needs of traditionally disadvantaged groups and individuals such as those in the LGBT community. The Committee on LGBT Rights addresses legal and policy issues that affect LGBT individuals.

The New York County Lawyers Association (“NYCLA”) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues is a committee of NYCLA—a not- for-profit membership organization of approximately 8,000 members committed to applying their knowledge and experience in the field of law to the promotion of the public good and ensuring access to justice for all. Founded in 1908, NYCLA was the first major bar association in the country to admit members without regard to race, ethnicity, religion or gender, and continues to pioneer tangible reforms in American jurisprudence. This amicus brief has been approved by the NYCLA Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues and has not been reviewed by the NYCLA Executive Committee.

The New York Office of the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (“NGLCCNY”), an its affiliate the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (“NGLCC”), is the business voice of the LGBT community and is the largest global advocacy organization specifically dedicated to expanding economic opportunities and advancements for LGBT people. NGLCCNY’s membership contains hundreds of certified LGBT Business Enterprises, LGBT business owners, LGBT employees of major corporations, and allies across all industry sectors who all see the same moral and economic imperative in ensuring that Title VII’s protections extend to all LGBT employees and contractors nationwide.

Out & Equal Workplace Advocates is the world’s largest organization dedicated to achieving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender workplace equality. We collaborate with leading local, national, and global corporations, their executives, human resources professionals, employee resource groups, and individuals to provide leadership & professional development, education, and research to create a culturally accepting work environment free of discrimination. Out & Equal partners with nearly 800 Fortune 1,000 companies and many federal agencies to ensure everyone—regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—is treated equally at work.

The Women’s Bar Association of the State of New York (“WBASNY”) is the second largest statewide bar association in New York, with more 4,400 members in nineteen regional chapters. WBASNY’s membership includes jurists, academics, and practicing attorneys in every area of the law, including constitutional and civil rights, employment law, family and matrimonial law, and children’s rights. WBASNY’s primary mission is to ensure the advancement of equal rights and the fair administration of justice for all persons. It has been a vanguard for the rights of women, children, and LGBT persons for decades, and it has participated as an amicus in many cases supporting equal rights for all persons, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, including before the Second Circuit and U.S. Supreme Court in Windsor v. United States, 699 F.3d 169 (2d Cir. 2012), aff’d sub nom. United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013).

IN THE

Matthew Christiansen,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

—against—

Omnicom Group, Incorporated, DDB Worldwide Communications Group Incorporated, Joe Cianciotto, Peter Hempel, Chris Brown,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

The LGBT Bar Association

of Greater New York (LeGaL)

By: Gennaro Savastano, President

601 West 26th Street, Suite 325-20

New York, New York 10001

(212)353-9118

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 26.1, amicus curiae The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (“LeGaL”) certifies that it has no parent corporation and no corporation or publicly held entity owns 10% or more of its stock.

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York (a/k/a the New York City Bar Association), is a voluntary bar association with no parent corporation or subsidiaries, and no corporation or publicly held entity owns 10% or more of its stock. The New York City Bar Association has one affiliate, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York Fund, Inc.

The New York County Lawyers Association (“NYCLA”) has no parent corporation and no corporation or publicly held entity owns 10% or more of its stock.

The New York Office of the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (“NGLCCNY”), certifies that it has no parent corporation and no corporation or publicly held entity controls any of its operations.

Out & Equal certifies that it is a nonprofit organization and has no parent corporation.

The Women’s Bar Association of the State of New York (“WBASNY”) states that it is a statewide voluntary bar association incorporated in the State of New York, with no parent corporation, no corporation or publicly held entity owning 10% or more of its stock, and twenty-eight (28) subsidiaries and affiliates (consisting of one (1) direct subsidiary that is an IRC 501(c)(3) charitable foundation incorporated in New York; nineteen (19) affiliated regional chapters across New York, some of which are unincorporated and others of which are incorporated in New York; and eight (8) IRC 501(c)(3) charitable foundations or legal clinics that are subsidiaries of its chapters and incorporated in New York).

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS |

Page |

|

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS |

i |

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS |

iii |

|

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES |

iv |

|

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE |

1 |

|

ARGUMENT SUMMARY |

1 |

|

ARGUMENT |

2 |

|

2 |

|

5 |

Discrimination Based on Their Sexual Orientation |

7 |

|

CONCLUSION |

12 |

|

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE |

13 |

|

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE |

14 |

|

ADDENDUM: INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE |

15 |

|

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES |

|

|

Cases |

Page(s) |

|

Baldwin v. Foxx, EEOC DOC 0120133080, 2015 WL 4397641 (July 15,2015) |

3, 8, 11, 12 |

|

Christiansen v. Omnicom Grp., Inc., 167 F. Supp. 3d 598 (S.D.N.Y. 2016) |

1,8, 12 |

|

Christiansen v. Omnicom Grp., Inc., 852 F.3d 195 (2d Cir. 2017) (Katzmann, C.J., concurring) |

passim |

|

Dawson v. Bumble & Bumble, 398 F.3d 211 (2d Cir. 2005) |

7 |

|

Hively v. Ivy Tech Cmty. Coll, of Indiana, No. 15-1720,2017 WL 1230393 (7th Cir. Apr. 4,2017) |

6,7, 8 |

|

Holcomb v. Iona College, 521 F.3d 130 (2d Cir. 2008) |

3,4 |

|

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) |

5 |

|

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) |

3 |

|

Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015) |

5 |

|

Pension Ben. Guar. Corp. v. LTVCorp., 496 U.S. 633 (1990) |

3 |

|

Philpott v. New York, 16 Civ. 6778, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 67591 (S.D.N.Y. May 3, 2017) |

8 |

|

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) |

3 |

|

Prowel v. Wise Bus. Forms, Inc., 579 F.3d 285 (3d Cir. 2009) |

7 |

|

Simonton v. Runyon, 232 F.3d 33 (2d Cir. 2000) |

passim |

|

U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n v. Scott Med. Health Ctr., P.C., No. 16-225, 2016 WL 6569233 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 4, 2016) |

9 |

|

United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013) |

5 |

|

Videckis v. Pepperdine Univ., 150 F. Supp. 3d 1151 (C.D. Cal. 2015) |

9 |

|

Zarda v. Altitude Express, No. 15-3775,2017 WL 1378932 (2d Cir. Apr. 18,2017) |

4 |

|

Rules |

|

|

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 |

passim |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 |

i |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 29(d) |

13 |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(5) |

13 |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(6) |

13 |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B) |

13 |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 32(f) |

13 |

|

Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(1)(B) |

6 |

|

Other Authorities |

|

|

Fourteenth Amendment |

5 |

|

B. Sears and C. Mallory, Williams Inst., Evidence of Employment Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation in State and Local Government: Complaints Filed with State Enforcement Agencies 2003-2007 (July 2011) |

10 |

|

B. Sears, et al., Williams Inst., Documenting Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity in State Employment (2009) |

11 |

|

EEOC, LGBT–Based Sex Discrimination Charges (Charges filed with EEOC) FY 2013-FY 2016, www.eeoc.gov (last visited Apr. 19,2017) |

11 |

|

Jennifer C. Pizer, et al., Evidence of Persistent and Pervasive Workplace Discrimination Against LGBT People: The Need for Federal Legislation Prohibiting Discrimination and Providing for Equal Employment Benefits, 45 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 715 (2012) |

10 |

|

Williams Inst., Annual Discrimination Complaints to State Agencies Prohibiting Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity, at 2, 5 (Nov. 2008) |

11 |

INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici are a coalition of voluntary bar associations and nonprofit organizations united in their commitment to protecting the rights of LGBT individuals and the prevention of workplace discrimination and harassment of all forms. Detailed statements of interests are in the addendum following this brief.

ARGUMENT SUMMARY

Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is discrimination on the basis of sex prohibited under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(l) (“Title VII”). The panel in Christiansen felt constrained by prior outdated decisions from this Circuit and thus, in order to avoid reaching an irrational result, furthered a distinction between gender stereotyping and stereotyping based on sexual orientation that is vague at best, unworkable, and in reality does not exist. Christiansen v. Omnicom Grp., Inc., 167 F. Supp. 3d 598 (S.D.N.Y. 2016). Furthermore, the prior decisions on which the panel relied are in direct conflict with Supreme Court and Second Circuit case law. Consequently, the law as it stands in this Circuit is in disarray. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (“LGB”) employees deserve clarity with respect to their rights in the workplace, and the time is now ripe for this Court to clarify those rights. For the following reasons, this Court should grant rehearing en banc to overturn its outdated precedent.

ARGUMENT

The Court Should Reconsider Simonton Because It Relied on Outdated Law, Resulting in a Decision That Conflicts with Supreme Court and Second Circuit Precedent.

Sexual orientation discrimination constitutes sex discrimination under Title VII in three distinct circumstances: (1) when LGB individuals are treated in a way that would be different “but for” their sex; (2) when LGB individuals are treated less favorably based on the sex of their associates; and (3) when LGB individuals are treated less favorably because they do not conform to gender stereotypes, particularly in romantic relationships. Christiansen v. Omnicom Grp., Inc., 852 F.3d 195, 202 (2d Cir. 2017) (Katzmann, C.J., concurring). As acknowledged by Chief Judge Katzmann, this Court has not had the opportunity to address these compelling theories, which developed after Simonton v. Runyon, 232 F.3d 33 (2d Cir. 2000). See Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 203-06. Given the “evolving legal landscape,” reconsideration of Simonton is warranted, justifying en banc review. See id. at 202 (Katzmann, C.J., concurring).

First, Simonton was heavily informed by Congress’s refusal to expand Title VII protections and thus deserves revisiting. See 232 F.3d at 35. This Court reached the bare conclusion in Simonton that “Title VII does not prohibit harassment or discrimination because of sexual orientation” and, like other circuits, relied on Congressional inaction to infer Congress’s intent to exclude sexual orientation from Title VII. See id. However, the Supreme Court has stated that “[congressional inaction lacks persuasive significance because several equally tenable inferences may be drawn from such inaction, including the inference that the existing legislation already incorporated the offered change.” Pension Ben. Guar. Corp. v. LTV Corp., 496 U.S. 633, 650 (1990) (citation omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted). Accordingly, the reasoning on which Simonton relied is irreconcilable with Supreme Court precedent; therefore, this panel’s reliance on Simonton merits reconsideration.

Second, reconsideration of Simonton is warranted in light of the recognition of associational discrimination. The theory of associational discrimination has long been accepted. See, e.g., Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 7–8 (1967). This Circuit adopted associational discrimination in Holcomb v. Iona College, 521 F.3d 130 (2d Cir. 2008). While Loving and Holcomb addressed race-based associations, because each enumerated category under Title VII is treated “exactly the same[,]” the theory of associational discrimination applies “with equal force” to discrimination based on sex. See Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 243 n.9 (1989). Thus, an employee who alleges that “his or her employer took his or her sex into account by treating him or her differently for associating with a person of the same sex” alleges sex discrimination under Title VII. Baldwin v. Foxx, EEOC DOC 0120133080, 2015 WL 4397641, at *6 (July 15, 2015). Because Simonton predates Holcomb, this Court has not yet addressed how associational discrimination intersects with discrimination on the basis of same-sex associations. This conflict in Second Circuit case law warrants a fresh examination of Simonton and en banc review.

Third, the Court should use the en banc opportunity presented here to address the modem approach—that sexual orientation discrimination is a type of gender-stereotyping under Title VII. As Chief Judge Katzmann noted, “fundamentally, carving out gender stereotypes related to sexual orientation ignores the fact that negative views of sexual orientation are often, if not always, rooted in the idea that men should be exclusively attracted to women … as clear a gender stereotype as any.” Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 206. Yet, “[t]he binary distinction . . . between permissible gender stereotype discrimination claims and impermissible sexual orientation discrimination” created by Simonton persists, complicating pleadings and disregarding the strong overlap between gender stereotypes and sexual orientation discrimination. Id. at 205. The resulting burden on LGB plaintiffs was recently demonstrated in Zarda, where this Circuit upheld dismissal of a gay plaintiffs gender-stereotyping claim “without analyzing whether [the plaintiff] could rely on a ‘sex stereotype’ that men should date women.” Zarda v. Altitude Express, No. 15-3775, 2017 WL 1378932, at *2 (2d Cir. Apr. 18, 2017). Accordingly, this Court should reconsider Simonton and acknowledge the “gender stereotype at play in sexual orientation discrimination.” Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 206 (Katzmann, C.J., concurring).

The legal landscape surrounding LGB rights has overwhelmingly changed since Simonton. Simonton predates the Supreme Court’s decisions in Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 578 (2003) (finding unconstitutional Texas’s criminalization of same-sex intimacy), United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675, 2679 (2013) (finding unconstitutional DOMA’s definition of marriage as between a man and woman), and Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584, 2607-08 (2015) (holding that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry, as protected under the Fourteenth Amendment). As reasoned in Obergefell, “[i]f rights were defined by who exercised them in the past, then received practices could serve as their own continued justification and new groups could not invoke rights once denied.” 135 S. Ct. at 2602.

The panel’s decision and its reliance on Simonton conflicts with Supreme Court and Second Circuit precedent. In light of this and the changing legal landscape surrounding LGB issues, the Second Circuit should reconsider Simonton and grant en banc review.

Roughly one week after the panel’s decision, the Seventh Circuit published its groundbreaking decision in Hively, where it held for the first time that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a form of sex discrimination under Title VII. See Hively v. Ivy Tech Cmty. Coll, of Indiana, No. 15-1720, 2017 WL 1230393, at *1 (7th Cir. Apr. 4, 2017). Hively is now in direct conflict with the decision of this panel. Accordingly, en banc review is warranted to address an issue of exceptional importance: whether Title VII’s bar on sex discrimination covers claims of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. See generally Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(1)(B).

In Hively, the Seventh Circuit held that a plaintiff who alleges discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation can put forth a valid claim of sex discrimination under Title VII. 2017 WL 1230393, at *1. In finding that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation constitutes a form of sex discrimination covered by Title VII, the Seventh Circuit stressed that it was not “amending” Title VII to add a new protected category, but was rather interpreting “what it means to discriminate on the basis of sex, and in particular, whether actions taken on the basis of sexual orientation are a subset of actions taken on the basis of sex.” Id. at *3. Ultimately, the Seventh Circuit was convinced that Title VII encompasses sexual orientation discrimination under two alternative theories: (1) the “comparative method,” where courts attempt to isolate the significance of a plaintiff’s sex in an employer’s decision; and (2) the associational discrimination theory.

Hively’s unequivocal holding overruled prior Seventh Circuit precedent. The panel here, however, concluded that it was bound by existing precedent and lacked the power to reconsider Simonton. Consequently, the panel’s decision stands in direct conflict with the Seventh Circuit’s en banc decision in Hively, and should therefore be reconsidered.

III. The Panel Decision’s Unworkable Approach Leaves LGB Employees Without Reassurance That They Are Protected from Illegal Discrimination Based on Their Sexual Orientation.

In continuing to draw a line between sexual orientation and sex-based discrimination claims, the panel has furthered a fallacious distinction. The panel’s decision would have district courts “independently evaluate the allegations of gender stereotyping” from allegations of stereotyping based on sexual orientation. Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 201 n.2. However, as the Chief Judge noted, courts throughout the country have grappled with this distinction and found it unworkable. Id. at 205; see also, e.g., Prowel v. Wise Bus. Forms, Inc., 579 F.3d 285, 291 (3d Cir. 2009) (“[T]he line between sexual orientation discrimination and discrimination ‘because of sex’ can be difficult to draw.”); Dawson v. Bumble & Bumble, 398 F.3d 211, 217 (2d Cir. 2005) (finding it “often difficult to discern” between allegations based on sexual orientation discrimination and those based on sex stereotyping, because “the borders [between these classes] are so imprecise”). Yet, the panel’s decision remands the plaintiff’s claim to the district court with the instruction to apply a framework that the district court has already found incoherent. See Christiansen, 167 F. Supp. 3d at 620 (“The lesson imparted by the body of Title VII litigation concerning sexual orientation discrimination and sexual stereotyping seems to be that no coherent line can be drawn between these two sorts of claims.”).

The confusion among courts surrounding this artificial line-drawing led the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) to throw out the distinction altogether. The EEOC’s official position is now that “an allegation of discrimination based on sexual orientation is necessarily an allegation of sex discrimination under Title VII.” Baldwin, 2015 WL 4397641, at *5. The EEOC reached this conclusion because, among other reasons, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation inevitably involves stereotypes about the proper gender roles in romantic relationships—namely, that men should only date women and vice versa.

Since Baldwin, numerous courts have gone beyond merely lamenting this distinction as unworkable, and have now coalesced to condemn the distinction as an artificial judicial construct with no basis in reality. See, e.g., Philpott v. New York, No. 16 Civ. 6778, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 67591 (S.D.N.Y. May 3, 2017) (“I hold that plaintiff’s sexual orientation discrimination claim is cognizable under Title VII.”); see Hively, 2017 WL 1230393, at *5 (concluding that the line between sexual orientation discrimination and sex-stereotyping claims “does not exist at all”); U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n v. Scott Med. Health Ctr., P.C., No. 16-225, 2016 WL 6569233, at *6 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 4, 2016) (describing the distinction between sexual orientation discrimination and sex stereotyping as “a distinction without a difference” and concluding that no line separates the two); Videckis v. Pepperdine Univ., 150 F. Supp. 3d 1151, 1159 (C.D. Cal. 2015) (“[T]he Court concludes that the distinction is illusory and artificial, and that sexual orientation discrimination is not a category distinct from sex or gender discrimination.”).

Additionally, under the panel’s framework, LGB employees who face illegal discrimination in the workplace can only seek protections under Title VII if they assert a gender stereotyping claim. This result permits (and perhaps even encourages) employers to claim that they did not discriminate against an employee because of gender stereotypes, but rather, simply because of the employee’s sexual orientation. Not only is this illogical, but also as the panel acknowledged, it has become “especially difficult for gay plaintiffs to bring” gender stereotyping claims. See Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 200 (citations omitted).

Moreover, Title VII protections should extend to all LGB employees, not just a subset who survive scrutiny within a false judicial construct. The law as it currently stands leaves LGB employees uniquely vulnerable to illegal employment discrimination, without the reassurance that they are protected from the evils that Title VII aims to protect against. Indeed, the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law has gathered studies demonstrating the impact of sexual orientation discrimination on LGBT employees. See Jennifer C. Pizer, et al., Evidence of Persistent and Pervasive Workplace Discrimination Against LGBT People: The Need for Federal Legislation Prohibiting Discrimination and Providing for Equal Employment Benefits, 45 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 715 (2012) (henceforth “Persistent Discrimination”). A 2008 national survey reported that 42% of LGB workers experienced some form of workplace discrimination or harassment related to their sexual orientation. See Persistent Discrimination at 722-23. A more recent 2011 study revealed that on a national level, the population-adjusted rate for sexual orientation-based discrimination complaints matches that of race-based discrimination claims at four claims per 10,000 workers, and is just short of the adjusted rate for sex-based discrimination complaints at five claims per 10,000 workers. See B. Sears and C. Mallory, Williams Inst., Evidence of Employment Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation in State and Local Government: Complaints Filed with State Enforcement Agencies 2003-2007, at 2 (July 2011).

Given the community’s vulnerability to discrimination, it is not surprising that the EEOC has reported a general upward trend in the number of sexual orientation-based discrimination complaints filed since the agency began tracking such information, including an increase from fiscal year 2015 (when Baldwin was issued) to fiscal year 2016. See EEOC, LGBT-Based Sex Discrimination Charges (Charges filed with EEOC) FY 2013-FY 2016, https://www.eeoc.gov/ (last visited Apr. 19, 2017). Similarly, a 2008 study reported an upward trend in the number of sexual orientation discrimination claims filed between 1999 and 2007 with the appropriate state agencies in Connecticut and New York. See Williams Inst., Annual Discrimination Complaints to State Agencies Prohibiting Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity, at 2, 5 (Nov. 2008). Corroborating this study’s finding, the New York State Division of Human Rights reported a similar increase of discrimination complaints on the basis of sexual orientation filed from 2003 to 2007. See B. Sears, et al., Williams Inst., Documenting Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity in State Employment at 15-67–15-68 (2009).

These studies highlight the dilemma faced by LGB employees, who seek to rely on anti-discrimination laws at roughly equivalent ratios to minority or female workers, but who find that protections for the LGB community are less likely to be enforced to the fullest extent of the law, as demonstrated by the history of this case. See Christiansen, 852 F.3d at 205–06 (Katzmann, C.J., concurring) (criticizing “binary distinction” created by Simonton in Title VII analysis as “exceptionally difficult” for fact finders and plaintiffs to manage); Christiansen, 167 F. Supp. 3d at 619 (recognizing the “difficulty of disaggregating [non-actionable] acts of discrimination based on sexual orientation from those [actionable acts] based on sexual stereotyping”). Further, the documented increasing rate at which these claims are being brought, particularly after Baldwin, will inevitably compound the confusion district courts face.

LGB employees, their employers, and their respective attorneys all need clarity with respect to this area of law. This Court needs to settle this uncertainty and should reconsider this case en banc to hold that discrimination based on sexual orientation is, in fact, sex discrimination under Title VII.

CONCLUSION

This Court should grant rehearing en banc and hold that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is discrimination on the basis of sex, as prohibited under Title VII.

The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (LeGaL)

601 West 26th Street, Suite 325-20

New York, NY 10001

(212) 353-9118

By: Gennaro Savastano

President

Amicus Curiae

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

This brief complies with the type-volume limitations of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B) and Fed. R. App. P. 29(d) because it contains 2,590 words, not including the addendum containing the “Interests of Amici Curiae” which is 669 words, as per the Motion for Leave to File an Oversized brief and Statement of Support, and excluding the parts of the brief exempted Fed. R. App. P. 32(f).

This brief complies with the typeface requirements of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(5) and the type style requirements of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(6) because it has been prepared in a proportional typeface using Microsoft Word in Times New Roman 14-point font.

Dated: May 5, 2017

The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (LeGaL)

601 West 26th Street, Suite 325-20

New York, NY 10001

(212)353-9118

By: Gennaro Savastano

President

Amicus Curiae

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on May 5, 2017, I electronically filed the foregoing brief with the Clerk of Court for the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by using the Court’s CM/ECF system. I certify that all participants in the case are registered CM/ECF users and that service will be accomplished by the CM/ECF system.

The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (LeGaL)

601 West 26th Street, Suite 325-20

New York, NY 10001

(212)353-9118

By: Gennaro Savastano

President

Amicus Curiae

ADDENDUM: INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE

The LGBT Bar Association of Greater New York (“LeGaL”) was one of the nation’s first bar associations of the LGBT legal community and remains one of the largest and most active organizations of its kind in the country. Serving the New York metropolitan area, LeGaL is dedicated to improving the administration of the law, ensuring full equality for members of the LGBT community, and promoting the expertise and advancement of LGBT legal professionals. LeGaL, whose membership includes attorneys that regularly represent LGBT employees in cases of employment discrimination, has a fundamental interest in ensuring that Title VII’s protections extend to all LGBT employees.

The New York City Bar Association (the “City Bar”) is a voluntary association of over 24,000 member lawyers and law students. Among other initiatives, the City Bar addresses unmet legal needs, especially the needs of traditionally disadvantaged groups and individuals such as those in the LGBT community. The Committee on LGBT Rights addresses legal and policy issues that affect LGBT individuals.

The New York County Lawyers Association (“NYCLA”) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues is a committee of NYCLA—a not-for-profit membership organization of approximately 8,000 members committed to applying their knowledge and experience in the field of law to the promotion of the public good and ensuring access to justice for all. Founded in 1908, NYCLA was the first major bar association in the country to admit members without regard to race, ethnicity, religion or gender, and continues to pioneer tangible reforms in American jurisprudence. This amicus brief has been approved by the NYCLA Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues and has not been reviewed by the NYCLA Executive Committee.

The New York Office of the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (“NGLCCNY”), an its affiliate the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (“NGLCC”), is the business voice of the LGBT community and is the largest global advocacy organization specifically dedicated to expanding economic opportunities and advancements for LGBT people. NGLCCNY’s membership contains hundreds of certified LGBT Business Enterprises, LGBT business owners, LGBT employees of major corporations, and allies across all industry sectors who all see the same moral and economic imperative in ensuring that Title VII’s protections extend to all LGBT employees and contractors nationwide.

Out & Equal Workplace Advocates is the world’s largest organization dedicated to achieving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender workplace equality. We collaborate with leading local, national, and global corporations, their executives, human resources professionals, employee resource groups, and individuals to provide leadership & professional development, education, and research to create a culturally accepting work environment free of discrimination. Out & Equal partners with nearly 800 Fortune 1,000 companies and many federal agencies to ensure everyone—regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity—is treated equally at work.

The Women’s Bar Association of the State of New York (“WBASNY”) is the second largest statewide bar association in New York, with more 4,400 members in nineteen regional chapters. WBASNY’s membership includes jurists, academics, and practicing attorneys in every area of the law, including constitutional and civil rights, employment law, family and matrimonial law, and children’s rights. WBASNY’s primary mission is to ensure the advancement of equal rights and the fair administration of justice for all persons. It has been a vanguard for the rights of women, children, and LGBT persons for decades, and it has participated as an amicus in many cases supporting equal rights for all persons, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, including before the Second Circuit and U.S. Supreme Court in Windsor v. United States, 699 F.3d 169 (2d Cir. 2012), aff’d sub nom. United States v. Windsor, 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013).

Footnotes:

1 The Boards of Directors of WBASNY and its 19 affiliated chapters include attorneys who are judges, court attorneys, or otherwise affiliated with courts in New York. No WBASNY members who are judges or court personnel participated in WBASNY’s vote to join in this matter as amicus or in the drafting or review of this brief.

2 WBASNY’s affiliates are: Chapters – Adirondack Women’s Bar Association; The Bronx Women’s Bar Association, Inc.; Brooklyn Women’s Bar Association, Inc.; Capital District Women’s Bar Association; Central New York Women’s Bar Association; Del-Chen-O Women’s Bar Association, Finger Lakes Women’s Bar Association; Greater Rochester Association for Women Attorneys; Mid-Hudson Women’s Bar Association; Mid-York Women’s Bar Association; Nassau County Women’s Bar Association; New York Women’s Bar Association; Queens County Women’s Bar Association; Rockland County Women’s Bar Association; Staten Island Women’s Bar Association; The Suffolk County Women’s Bar Association; Westchester Women’s Bar Association; Western New York Women’s Bar Association; and Women’s Bar Association of Orange and Sullivan Counties. Charitable Foundations & Legal Clinic – Women’s Bar Association of the State of New York Foundation, Inc.; Brooklyn Women’s Bar Foundation, Inc.; Capital District Women’s Bar Association Legal Project Inc.; Nassau County Women’s Bar Association Foundation, Inc.; New York Women’s Bar Association Foundation, Inc.; Queens County Women’s Bar Foundation; Westchester Women’s Bar Association Foundation, Inc.; and The Women’s Bar Association of Orange and Sullivan Counties Foundation, Inc.

3 The Boards of Directors of WBASNY and its 19 affiliated chapters include attorneys who are judges, court attorneys, or otherwise affiliated with courts in New York. No WBASNY members who are judges or court personnel participated in WBASNY’s vote to join in this matter as amicus or in the drafting or review of this brief.